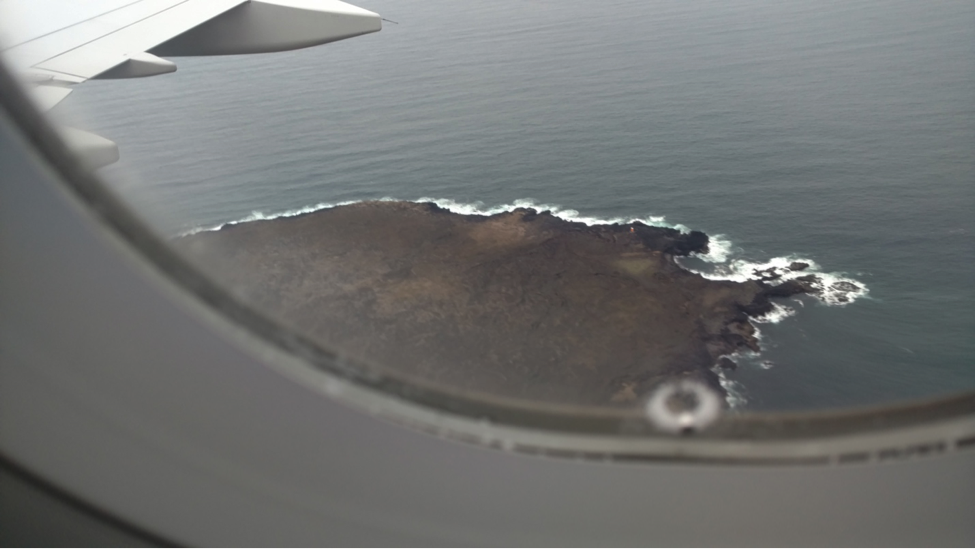

My first glimpse of Iceland came through the airplane window: a stark brown edge of land in bas-relief against a clean gray ocean. It’s an appropriate introduction to the island. At a glance, the landscape seems desolate, almost dull: a moonscape without the benefit of outer space to heighten it.

But look for a little longer. Even at its most nondescript, the Icelandic landscape pulses with a hidden excess. This feeling first struck me as we rode the Flybus from Keflavík International Airport to Reykjavík. The lava fields surrounding us seemed eerily quiet, as if they were keeping a secret. In a sense, they were and are: The earth of Iceland is fierce. It’s one of the most active volcanic regions in the world, though you would never know it from the docility of the visible landscape.

To our right were the mountains of the Highlands, a raw wilderness prone to floods and eruptions that occupies most of the island’s interior. Regardless of where you are, you can almost always see these mountains. The interior constantly looms just out of frame, contributing to the sense of barely contained power one feels at every moment of every day in Iceland: Somewhere, a volcano may be erupting, a glacial river may be sweeping a 4×4 away.

After landing, we purchased Birkir at the first liquor store we saw. Birkir is a relatively new type of Icelandic schnapps infused with birch, with a reminiscent taste of maple syrup–although I wouldn’t suggest pouring it over your pancakes. Or well, maybe you could…It’s just that delicious, and it comes bottled with a birch twig inside. The Icelandic version of a tequila worm, only with more class and a far better aroma.

You can’t visit Iceland without visiting Reykjavik, and there are two places you have to visit. The first is the Culture House, which doesn’t do a great job of advertising itself. You’d be forgiven for thinking it nothing more than a rare manuscript library, but the Culture House is actually home to a stunning exhibition called Points of View, which weaves together artwork and artifacts from Iceland’s birth in the 9th century to the present in order to tell the story of the country’s cultural identity. I walked in a tourist. I left – well, I left still a tourist, but a profoundly changed tourist, one who ached to up and move to Iceland permanently.

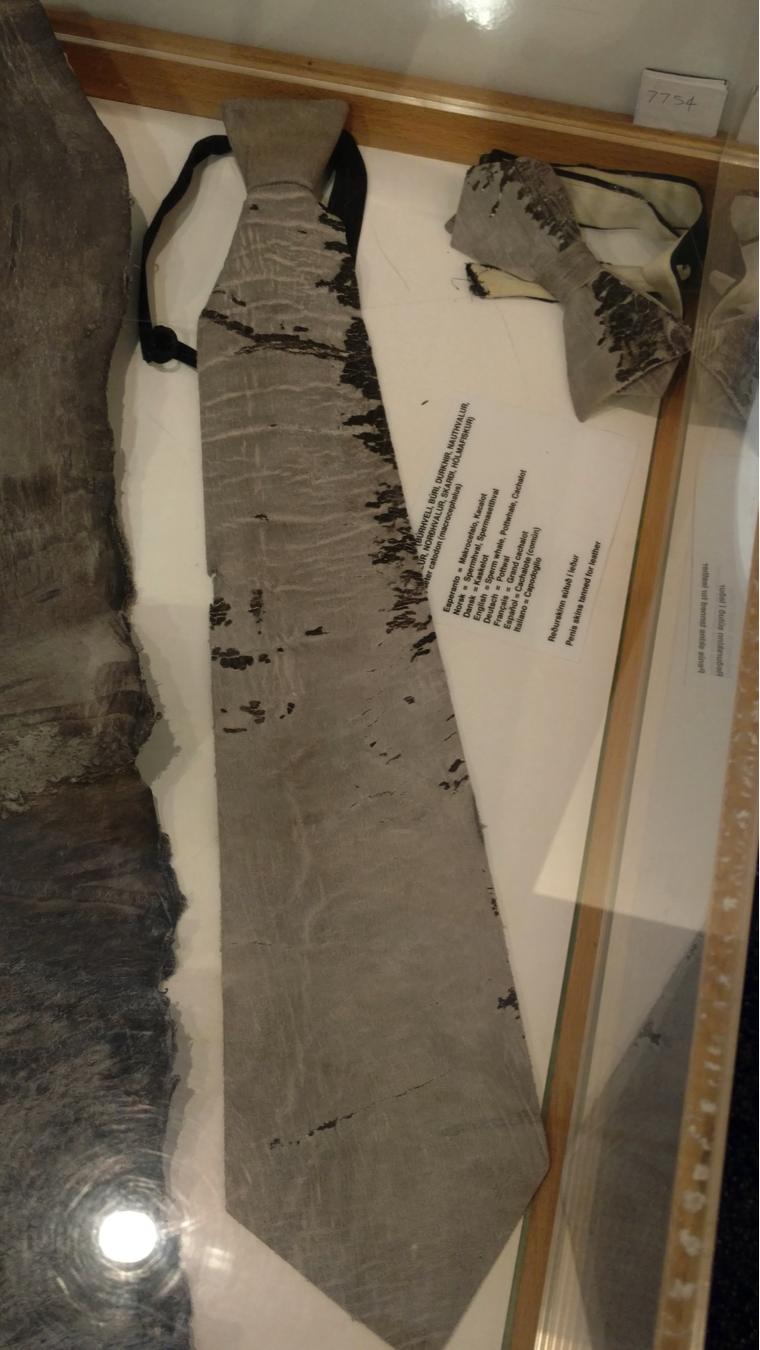

The second is the Icelandic Phallological Museum, which is exactly what it sounds like: a museum dedicated to phalluses. Among the 280 specimens are an orca’s package, a reindeer’s tool, and a, yes, a human member. A phallus museum may not be everyone’s idea of a perfect day, but at the very least, you’ll get some excellent pictures.

(Ties made from the skin of a blue whale’s penis. I did say you’d get some excellent pictures.)

If you’re unsure of why so many Icelandic people believe in elves – or Huldufólk as they’re known in the country; the name translates to “hidden people” – visit Þingvellir, anglicized as “Thingvellir”. The site of the first Icelandic parliamentary proceedings in 930, Þingvellir is also one of two places on Earth where one can observe the drifting of tectonic plates.

Walking through the rifts caused by the the North American and Eurasian Plates pulling away from one another, I felt as if I were at the nexus of two worlds. It seemed not only reasonable, but necessary that the faults and crevices hide something more, something beyond myself (that sense of excess again).

Dramatic, yes – but Iceland’s is a dramatic landscape. It demands revelation.

(Drekkingarhylur at Þingvellir)

As far as dining goes, the Icelandic diet consists mainly of fish, dairy, bread, and preserves. This is by no means a bad thing–that is, of course, if you aren’t gluten-free|dairy-free|don’t eat meat. I, unfortunately, am a vegetarian. My wife, on the other hand, is a gluttonous, meat-eating, cheese-stuffing, beauty–I don’t know how or why she ever married me, but anyway.

My favorite meal of the entire trip, eaten at the Vogafjós guesthouse on the eastern shore of Lake Mývatn, also happens to be a prime illustration of Icelandic dining. To wit:

– smoked arctic char;

– rúgbrauð, also called “geysir bread” (a rich, cakelike rye bread that is baked by geothermal heat – as in, you dig a hole near a hot spring, put your dough inside, and come back in 24 hours to find a fully baked loaf);

– farm-made mozzarella cheese (although Swiss seemed more popular in most of the restaurants we ate at);

– an omelet;

– and skyr, a style of low-fat, high-protein yogurt that tastes better than any other yogurt you’ve ever had, especially if you have it with milk (my wife describes it as “like cheesecake, but good for you”).

No treatment of Icelandic food would be complete without mentioning kæstur hákarl, a.k.a., fermented Greenland shark. I recommend trying it, but only for the experience and not in public. We bought a small container at the market and brought it to our hotel. It’s difficult to accurately convey the taste, but imagine drinking a concoction made of equal parts ammonia, urine, and salt.

There is a reason that kæstur hákarl is traditionally chased with a shot of brennivín (a strong schnapps flavored with caraway).

Depending on whom you ask, Dimmuborgir is home to either Satan or the Yule Lads (essentially the Icelandic Santa Clause, except there are 13 of them and they do things like steal your sausages and slam doors. Also, their mother is a troll and they leave potatoes for bad children instead of coal. I really want to celebrate Christmas in Iceland when I have kids).

Like so much of Iceland, it’s not hard to see why so Dimmuborgir has accrued a crust of folklore: It is essentially a forest of freestanding lava pillars. In some areas, it resembles the ruins of an otherworldly castle.

As I climbed into a hollow circle in one of the pillars, I half believed – if only for a moment – that I was climbing out of this world and into another. So much of Iceland feels like it’s on the brink. If you could just find the right hole to slip through –

(Cave at Dimmuborgir)

I’m sure it’s different for the Icelanders themselves. No one can spend their entire life living in a liminal space. The existential stress would be too much. So like the smell of your own apartment, you learn to go blind to it.

But then again, I don’t know.

While driving from Akureyri to Mývatn, we pulled into a rest stop to get some gas. There, maybe less than half a mile from the pumps, was Goðafoss, the “waterfall of the gods,” a 40-foot wall of falling river. Carrying out the quotidian – filling your gas tank, walking to work, writing a rent check – against that kind of backdrop: Is that something you can ever get used to? I suppose you’d have to. Otherwise, the check would never get written. You’d be too busy staring slack-jawed at a waterfall.

(Goðafoss)

Matthew Kosinski is a writer and poet who lives in Jersey City. He is currently an MFA candidate at the New School in New York City, and is an editor at Recruiter.com. He is also a co-founder of the online literary magazine, Politics and Poems. You can find more of his work at www.matthewkosinski.com, and on twitter @matthew_vmk

Save up to 60% on Business Class. Call 1-800-435-8776

Save up to 60% on Business Class. Call 1-800-435-8776

Leave A Comment